I came across the following Agony Aunt letter thanks to the brilliant Boorloo Boodja Facebook page, an invaluable resource for WA Aboriginal history. What makes the page so compelling is its focus on personal, grounded stories that cut through the generic narratives often served up (by white folk like me) about Aboriginal people in this state. It’s a space for truth-telling, nuance, and lived experience.

Their post about a 1945 letter and an Agony Aunt’s response was thoughtful and well-framed. But I couldn’t help feeling that one key point had slipped through the cracks. In being rightly sensitive to the needs of their readership, the editor chose to edit the original letter for publication, removing the scientific-racist terminology used to describe mixed-race people. That’s absolutely their call, and in most cases, it’s the right one. But in this instance, it slightly muddied the waters.

Those uncomfortable terms (“quadroon”, “octoroon”, “near-white”) aren’t just offensive relics. They’re central to understanding how race was constructed, policed, and lived in 1940s Perth. Sanitising them, even with good intentions, risks losing sight of the racial logic the Agony Aunt was both using and very slightly challenging. So I went back to the original letter on Trove, and what follows is my take on what it reveals. This is not intended as a criticism of Boorloo Boodja, but as an addition to their retelling of this event.

Agony‑aunt letters have always lived in a curious space between truth and storytelling. Editors often shaped or combined multiple experiences into a single “letter” so they could address a real social problem without exposing any one individual.

With that in mind, the 1945 exchange between “Mary Ferber” (the pen name of Perth journalist Bonnie Giles) and a woman seemingly self-described as a “quadroon” is still an extraordinary snapshot of Australian racial attitudes at the end of the war.

“M.I.” describes herself using the racial categories of the time, explaining that she and her children are mixed‑race and facing constant discrimination in Perth’s housing market. Agents refuse to rent to her, country towns turn her away, and she feels trapped by prejudice she can’t escape. She writes with frustration, dignity, and a clear sense that the system is stacked against her. Her question to the Agony Aunt is essentially: What can someone like me do when society won’t give us a fair chance?

Ferber acknowledges the discrimination and treats the letter seriously. She insists the writer is “not Aboriginal” but “Australian with a handicap”, revealing the racial hierarchy she carried in her thinking. Ferber encourages mixed‑race people to form an association for mutual support and refuses to pity the writer, instead affirming her worth.

What stands out is how mixed the tone is: sympathetic, paternalistic, a tiny bit radical, and deeply constrained by the racial thinking of the time.

Ferber tries to distance Australia from the harsher racism of the United States, claiming that white Australians are guilty of “stupidity” rather than “active intolerance”. But this is an easy cop‑out. By pointing to the U.S. as worse, she gives white Perth a pass. Local racism isn’t worth worrying about because someone else is having it worse. It’s a classic deflection, and one that lets systemic discrimination off the hook.

But she does acknowledge discrimination as real, especially in housing, and treats the correspondent’s complaint as legitimate rather than inconvenient. Publishing the letter at all, giving a platform to a non‑white woman’s experience in a mainstream Perth newspaper, was not the norm for the era.

At the same time, her language reveals the limits of white liberalism in 1945. She draws a sharp line between “coloured Australians” (those of mixed race) and what she sees as Aboriginal people, implying that the latter sit outside her category of “Australian”. She uses blood‑quantum labels like “quadroon” and “octoroon” without question. She assumes assimilation into whiteness is the natural goal for those mixed-race Aborigines she sees as more civilised.

Yet she also encourages collective organisation among mixed‑race Australians, suggesting they form an association to advocate for themselves. That idea, in 1945, sits surprisingly close to civil‑rights thinking. And she refuses pity, insisting instead on dignity and capability.

So was her response progressive? By today’s standards, no. It’s steeped in racial hierarchy and paternalism. But for a white newspaper columnist in 1945, it sits on the more sympathetic and reform‑minded end of the spectrum. It recognises discrimination, rejects contempt, and treats the correspondent as someone whose voice deserves to be heard.

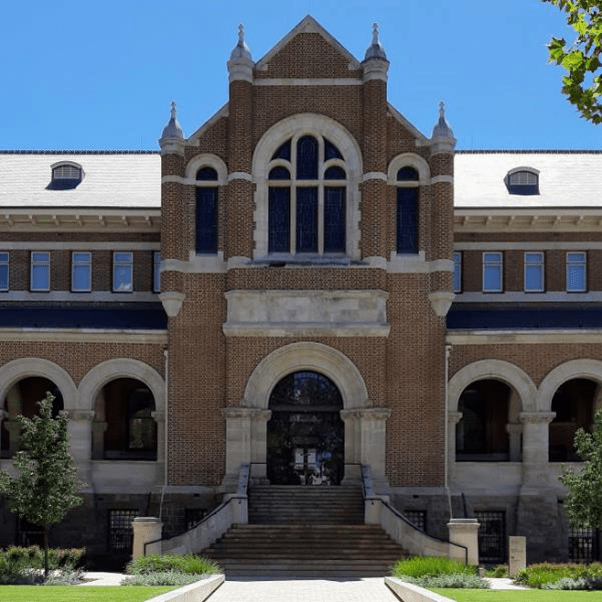

In other words: it’s a window into a society beginning to see its own prejudices, but not yet ready to dismantle them. In the end, it’s worth remembering that “Mary Ferber” was remarkably consistent in her own version of anti‑racism. She wasn’t just talk. A few years after this letter, she publicly campaigned for an Aboriginal women’s hostel in Mt Lawley at a time when local residents were loudly, angrily opposed to the idea. She took heat for it, and she didn’t back down.

But she also never escaped the racial logic of her era. Her worldview divided Aboriginal people into two imagined categories: the “good”, mixed‑race individuals who could be welcomed as fellow Australians, and the “full‑blood” people she assumed were destined to remain outside mainstream society. It’s a framework that feels deeply uncomfortable now, and rightly so. Yet it was a common mid‑century belief among white progressives who saw themselves as allies.

Like most things in the past, it’s messy. It doesn’t sit neatly with us today. And it’s exactly why Aboriginal voices from this era must be the priority: voices that speak from lived experience rather than from the well‑meaning distance of white commentary.

That’s precisely what Boorloo Boodja excels at: bringing forward those personal, grounded stories that shift the centre of gravity back to where it belongs. We can acknowledge Ferber’s efforts, and her limits, without turning her into a white saviour, and without losing sight of the people whose stories matter most.