As big as a whale

All stories must start somewhere, so we will start with a horse named Gold and Black. The twenty-something rider on top of Gold and Black was one of Western Australia’s most skilled equestrians, Bertha Elvina Locke, although everyone called her Daisy. Daisy was to suffer several horse-related accidents throughout her life, but she just treated these as a risk of the sport. It is quite clear that this young woman was the sort to take life’s ups and downs in her stride.

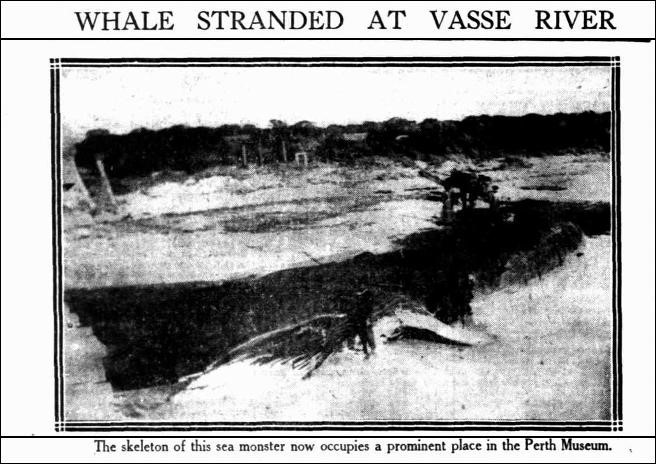

Daisy lived at Wonnerup or, to be more specific, at Lockville Farmhouse, a picturesque building with an original wattle and daub cottage and a later two-storey limestone extension. It was probably slightly unusual in that part of the state for Daisy to have another hobby: reading mining manuals. She also discovered the whale which was Perth Museum’s most famous exhibit for more than a century, although it now lies hidden in a Welshpool warehouse awaiting a new home.

Picture Daisy riding one her horses along Lockeville Beach, accompanied only by her large white parasol, lined with green, on Tuesday 17 August 1897. This is when Miss Locke came to see a giant whale stranded near the jetty. Turning her horse around, she galloped to Wonnerup House to seek her uncle’s assistance. Together with another man, they went out in a small boat, harpooned the great creature, and securely anchored it to the shore. Daisy, with the knowledge gained from her mining manuals that everything of value must be within four pegs, decided to stake the beast in case anyone else claimed it. Three long pieces of wood were found, but the fourth corner required the sacrifice of her much-loved parasol. Unhappily for the whale, though, it took a week to die after the harpooning.

When the news reached Busselton the next day, large crowds came out to see the amazing discovery. Among these was Water Police Constable Tonkin, an ex-whaler, who valued the 26-metre creature’s oil alone at £200. Even if Constable Tonkin was right, Daisy was never to financially benefit from her staked-out claim since no one in the area had the skills or the equipment to extract the valuable substance. Instead it was proposed to offer the whole whale to the Perth Museum, and the locals thought this would be a simple matter since the railway line was less than two miles away.

The museum must have been delighted with the offer, given how dull recent donations had been: a report from the Department of Mines, two coins, a drawing of a bore in the Collie coalfields, three pebbles, three newts, and two caterpillars. As it turned out, it was much more complicated to relocate a gigantic whale than to receive two caterpillars. But that was no longer Daisy’s problem, since the responsibility now fell on the shoulders of the museum’s taxidermist, Herman Franz Otto Lipfert.

But his story has to wait for another day.

[…] brief recap on yesterday’s post: a Busselton whale was claimed by Daisy Locke in 1897. It was agreed to donate it to the museum in […]

LikeLike