Why grandma, what a big mouth you have…

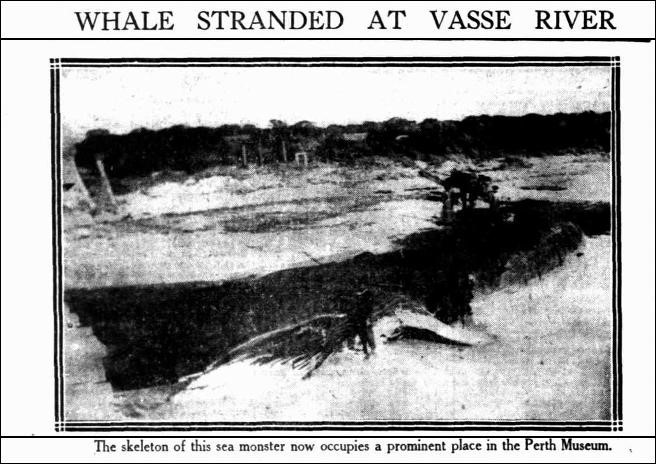

A brief recap on yesterday’s post: a Busselton whale was claimed by Daisy Locke in 1897. It was agreed to donate it to the museum in Perth, so it was now an issue for taxidermist Herman Franz Otto Lipfert to work out what to do with it. Now read on…

In later life, Otto Lipfert was described as a bespectacled, white-smocked, fuzzy-haired, lightly-built man, looking considerably less than his seventy-three years of age, with a modesty and manner out of place in modern society. He was said to be soft of speech, unruffled in demeanour, unhurried in manner, painstaking and methodical. In other words, Perth folk found him a stereotype of German efficiency.

Otto had arrived from Germany at the right time, 1892. A trained furrier and taxidermist, he was exactly what a new museum needed. Chronically underfunded, the museum eventually offered him a month-to-month contract in 1895 on a salary of £210. Throughout his decades working there, his wage was barely increased, and he had to supply all his own tools of the trade and work in pitiful spaces, originally just a wooden shed out the back.

So how do you prepare a creature that’s been rotting on a beach for some weeks? The annoying thing about the whale, at least for the taxidermist, is that its carcase cannot be preserved. The skin is very thin and attached to blubber up to five centimetres thick. It’s impossible to scrape the blubber away and preserve the surface.

So Otto supervised a man named Hunt and two Japanese gentlemen to remove all the flesh before the bones could be taken above the high-water mark. It must have been an awful job to undertake. The bones were left there for a few months, to let all the remaining soft body decay and the skeleton to bleach in the sun. The Bunbury Herald blandly reported in May 1898 that the bones had been “sent for exhibition at the Perth museum” from Bunbury Railway Station, but this does not even begin to describe the complexity of the operation.

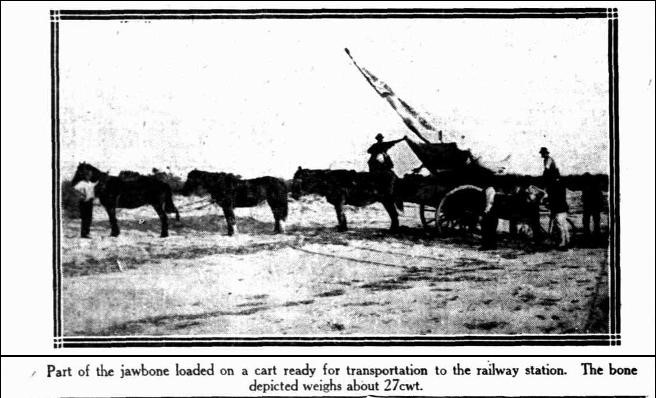

Otto made another trip down to Locke’s farm, and got busy numbering the bones. Then he supervised the loading of them. The skull alone weighed 1,370 kg, while each of the lower jaw bones weighed 813 kg, so the job of transporting them to the railway line was no easy matter. It needed six men with winches just to place them in position on the wagons. To rail them to Perth, five and ten tonne trucks were needed. “It was not easy to shift,” Otto understated some years later.

After this, the whale needed to be installed as an exhibit at the WA Museum. But that’s a story for another day.