They appear to have accidentally built Perth on a load of lakes

Well, they do have names. And stories behind them. As we start to get things together for the Dictionary of Perth website, it’s fairly evident that one thing that fascinates people is the origin of street names. Having a story to go with your road makes it just a little bit more magical.

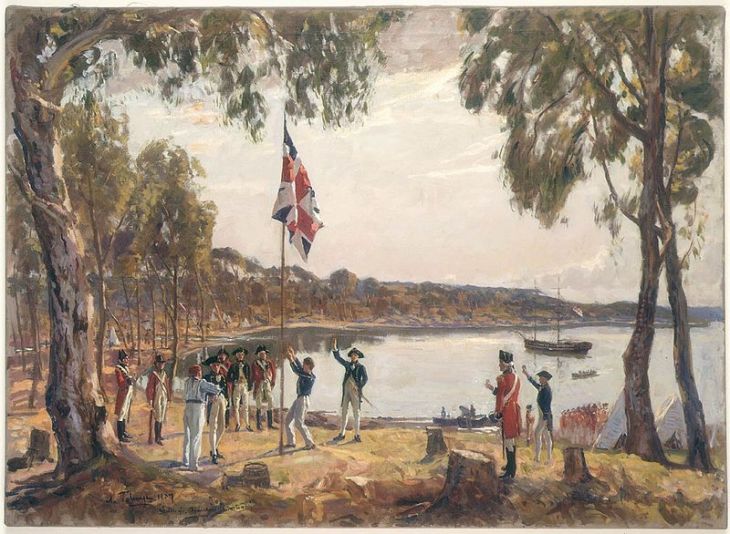

The first complete record of street names in the city was made on 12 February 1838, when an official map was issued. Perth was less than ten years old and there were very few decent roads in existence.

So, without further ado, we’ll get the ball rolling with the people behind some of the larger streets in Perth.

Aberdeen Street

Received its name in honour of George Hamilton Gordon, Earl of Aberdeen and Prime Minister of England in 1831.

Newcastle Street

The Duke of Newcastle, Secretary of State for the Colonies from 1852 to 1854. An old street named Ellen Street after Lady Ellen Stirling, wife of the Governor, extended from Lake Street to Stirling Street is now part of Newcastle Street. In the early days, the road east of Stirling Street was called Mangles Street, after Ellen’s maiden name.

Beaufort Street

Named after Irishman Rear-Admiral Sir Francis Beaufort, who in 1829 was the Admiralty’s chief map-maker.

One of his groupies was John Septimus Roe, who first planned Perth, and who not only named Beaufort Street after him but also Francis Street in Northbridge.

In an earlier version of this post we claimed it was named after Lord Charles Henry Somerset, second son of Henry, 5th Duke of Beaufort. This turns out to be a 19th century urban myth.

Goderich Street

Originally extended towards town as far as Barrack Street. It was named after Viscount Goderich, Prime Minister of England in 1827-28 and Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1830-1833.

Murray Street

Named after Sir George Murray, Secretary of State for the Colonies from 1828 to 1830.

James Street

Honours the Christian name of Sir James Stirling

Mount’s Bay Road

Shown on the 1838 map as Morgan Street, it took its name from J. Morgan, Resident Magistrate of Perth in 1832, and who was tasked with making this road.

Pier Street

Originally extended from Perth’s first landing stage northwards through the present grounds of Government House.

Stirling Street

The surname of the State’s first Governor

St. George’s Terrace

In honour of the patron saint of England.

William Street

Originally King William-street, after William IV. During the years the ‘King’ was dropped and when this was done, King Street came into being.

Hay Street

Named after Robert William Hay, Permanent Under-Secretary for Colonies when Perth started. East of Barrack Street, Hay Street was once known as Howick Street, after Lord Howick, an official in the Colonial Office.

Lord Street

Lord Howick, Lord Wellington and Lord Goderich having given their names to three parallel streets, Lord Street probably received its name from its close connection with the three thoroughfares.

Adelaide Terrace

Named after Queen Adelaide, wife of William IV.

Barrack Street

The first barracks in the State were erected near the corner of Barrack Street and St. George’s Terrace.

Wellington Street

With the victories of Nelson and Wellington still fresh memories, many street names show how patriotic the early settlers were. Nelson Crescent, Horatio Street, Nile Street (after a famous campaign), Waterloo Crescent, and Trafalgar Road. Bronte Street is so called because Lord Nelson was Duke of Bronte.

West Perth streets

In 1877-78, Col. R. T. Goldsworthy, Colonial Secretary of the State, who served during the First War of Independence in India (then called the Indian Mutiny) fixed the names of several Perth streets after this event. Colin Street after Sir Colin Campbell, Delhi Street, Havelock Street after General Sir Henry Havelock and Outram Street after General Sir James Outram.