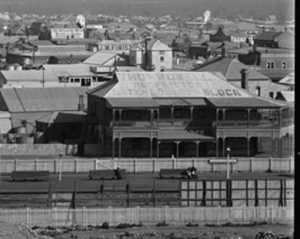

Darling Range Hotel in 1914

Nothing makes us sadder than the unnecessary loss of an old pub. Especially one that still has skimpies. And by skimpies, we obviously mean a long and interesting history. Yet lose it we might, if plans to demolish the Darling Range Hotel for yet another service station go ahead.

Built as the East Midland Hotel in 1905 for Thomas Wilkins, the site was chosen so patrons could sit on the balcony and watch the horses at the Helena Vale Racecourse. Naturally, it became very popular. In 1914 it was sold to a man with the wonderful name of Welbourne Keatley Lamzed, who arrived just in time to take advantage of a new source of customers: the men doing basic training at Blackboy Hill.

No one liked the way the YMCA was running the camp’s alcohol-free canteen, and a rival wet mess for the men was quickly shut down after wowsers complained to the newspapers that soldiers shouldn’t be allowed a pint after a hard day’s training. So the Darling Range Hotel, newly renamed and redecorated, was one of the few sources of beer for the men.

However, someone started a rumour that Mr Lamzed was (whisper it now) a German, and no patriot should be drinking in his venue. The rumour was, of course, a complete lie, Lamzed was born in East London, much to the relief of those doing their training. In fact, he had supplied the short-lived wet canteen at Blackboy Hill, and argued that men should drink at the camp, rather than coming to the Darling Range Hotel, since there would be less temptation to go AWOL after a few glasses.

And Lamzed said he didn’t really want all the new customers anyway, since he had bought the pub as a quiet retreat to live out an easy life after a career spent in the construction trade. As a side note, Lamzed had erected Boans first ever store, so he has more than one claim to fame.

But the wowsers won the day, the wet canteen stayed closed, and the Darling Range Hotel became the main drinking hole for those ANZACs about to serve overseas.

Today you drink in a new tavern built at the back of the old building, which has lost much of its charm with the loss of the verandahs. But that’s still no excuse for knocking over part of our military and boozing history. Go have a drink there. Take a selfie outside the original hotel, and tell JDAP to keep their planning paws off one more piece of our heritage.