Next time you drop into Petition, make sure to order something French. They have a Petit Chablis which has good reviews, so that’s on our must-drink list (yes, we have a must-drink list) when we take another look at George Temple Poole’s Old GPO building. This is now part of the Central Government Buildings or, as they are more commonly known, the Old Treasury.

One of the things architects fear the most, other than mislaying their designer glasses, is being seen as derivative. A difficult job to undertake is designing additions to an existing building or set of buildings. The new work has to complement the structures already there, but not copy them so closely that you don’t look an original architect. In other words, the architect must triumph over their predecessor, but not look too arrogant while doing so. This is a very difficult feat to pull off, but it is exactly what George Temple Poole achieved with his additions to the Central Government Buildings, which opened in 1890.

Poole was faced with a site which already had two older building, both designed by Richard Roach Jewell, and are now the wings along Barrack Street and Cathedral Avenue. These were proving completely inadequate for the needs of civil servants, and Poole was asked to link the two buildings with new offices and to include a post office while he was at it. His solution was so effective that some architectural critics believe he was simply showing ‘architectural good manners’ and respecting Jewell’s earlier work. He was most definitely not.

The only acknowledgement of the existing buildings was to use Flemish bond brickwork, which is alternating ‘headers’ and ‘stretchers’, usually in two different colours. Speaking of colour, have a look at how the new bricks are completely different to the older ones. This is most noticeable in the third storey of each of the wings, since Jewell’s original buildings only had two floors and a flat roof. No attempt was made to match the shades of the bricks.

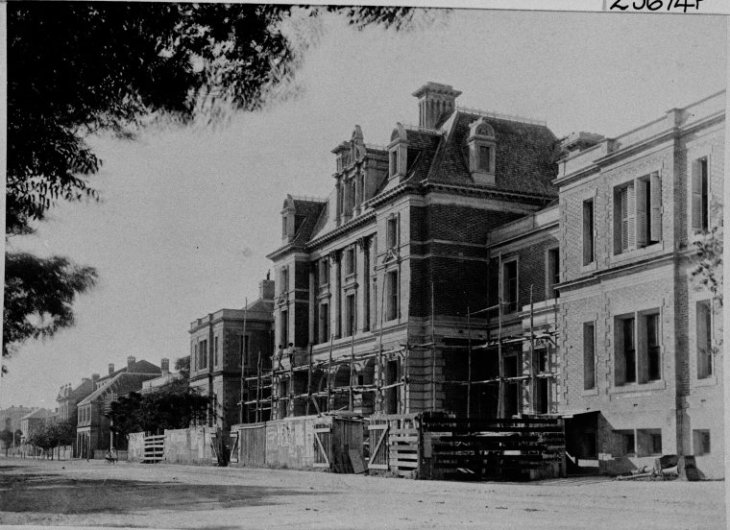

Under construction, 1889

The inspiration for the central element on St George’s Terrace was definitely French architecture. One possible model is the Hotel de Ville in Paris, which shows similar chimneys, Mansard rooflines, and dormer windows. But Poole did not copy this building, he just took some of the ratios and overall concept, adding in a little English Queen Anne style for the windows and other details. Poole was declaring that this was his building, and his alone.

To link the central element to the older buildings, the setbacks either side of the middle gives more prominence to Poole’s contribution, and once again clearly shows what is old and what is new. Finally, the windows on Jewell’s portion were redecorated with the same design as the new ones, and when third storeys were added, they also got Mansard roofs. The new skin on Jewell’s earlier buildings transformed their character, making them just another part of Poole’s overall project. His project.

And it works. The style conformed to expectations for what a government building should look like, integrated existing buildings, and created what was the most impressive building in Perth at the time. Plus, this was no simple addition, it was a novel work, one which showed Poole could meet head on the circumstances he was faced with and triumph as an original architect. Not bad for a simple linking element.

And now for that glass of Petit Chablis to celebrate our unusual French(ish) building on St George’s Terrace.